In this application, if the data reader fails for some reason, we want to make sure the exception gets logged. We'll log to the file system to keep things simple, but we can use whatever logging system we'd like.

The Decorator Pattern lets us add functionality without changing existing classes.This article is one of a series about dependency injection. The articles can be found here: More DI and the code is available on GitHub: https://github.com/jeremybytes/di-decorators.

Behavior Without Logging

Before adding exception logging, let's look at the existing behavior of the application. For this, we'll remove the previous decorators and go back to our original object composition.

Composing the Objects

Here's the composition root for the application in the "PeopleViewer" project, App.xaml.cs file.

The code here is much different from what is in the GitHub project. The GitHub project uses all of the decorators. We'll look at that in a later article. To follow along with this article, you can replace the code in the "ComposeObjects" method with what we have here.

As a reminder, the "ComposeObjects" method has 3 steps. (1) It creates a ServiceReader; this is a data reader that gets data from a web service. (2) It uses the ServiceReader as a parameter to create a PeopleReaderViewModel; this view model has the presentation logic for the form. (3) It uses the view model as a parameter to create the MainWindow; this is the view that has the UI elements for the form.

Running the Application (Failure)

Since the application is configured to use the web service, let's see what happens when we run the application *without* starting the service.

If we run and then click the "Refresh People" button, we get the following result. (Note: if you are running in the debugger, the debugger will stop when an exception is thrown. Just press "Continue" or "F5" to keep going.)

The application gives us a pop-up message that comes from a global exception handler. The message does not tell us exactly what happened. It is generally a bad idea to show raw exception messages to our users. Instead, we should give them a message that is more appropriate.

The problem right now is that we are not logging the exception.

Logging the Exception

Since the exceptions come from the data reader, we'll use a decorator to intercept the exceptions so we can log them. For this, we'll create an ExceptionLoggingReader.

As a reminder, to create a decorator, we wrap an existing implementation of an interface and add our own behavior. Then we expose the same interface so that it looks like any other data reader.

Here is the IPersonReader interface (from the "Common" project, IPersonReader.cs file):

This is the interface that we want to wrap as well as implement.

Here is the code for our exception logging decorator (from the "PersonReader.Decorators" project, ExceptionLoggingReader.cs file):

The first thing to notice is that this class implements "IPersonReader", so it has the methods "GetPeople" and "GetPerson". This lets us plug this into our application just like any other data reader.

The constructor takes 2 parameters. The first is an "IPersonReader"; this is the data reader that we're wrapping, and we store it in a private field.

The second constructor parameter is an "ILogger". This will handle the logging calls, and we store this in a private fields as well. We'll look at the details of the logger in just a bit.

In the "GetPeople" method, we call the "GetPeople" method on the wrapped data reader. If the wrapped reader returns successfully, we pass along that value.

If the wrapped reader throws an exception, we log the exception and then rethrow it. This particular class is not designed to handle the exception; the exception will continue to bubble up the call stack until it hits our global exception handler. But we are intercepting the exception so that we can log the details.

The Logger Interface

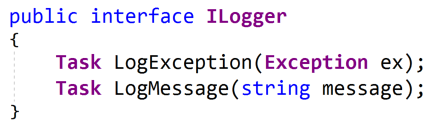

The ILogger interface has 2 methods (from the "Logging" project, ILogger.cs file):

Our logger implementations need to have methods to log an exception and to log a message.

As a side note, this is in a "Logging" project separate from the data reader and decorator projects. The idea is that the logger can be used by other parts of the application as well, so we have it is a location that can be easily shared.

A File Logger

For this application we will log to a file. So we have a FileLogger class that implements the ILogger interface. Here's the code (from the "Logger" project, FileLogger.cs file).

Since this implements that "ILogger" interface, it has both the "LogMessage" and "LogException" methods.

At the top of the class, we have a field to represent the log file. This is a hard-coded location: the application folder. So this will be in the same folder as the executable. The file name is also hard-coded: ExceptionLog.txt. We can parameterize these values if we need to, but this will get things working.

The "LogException" method uses a StreamWriter to write to a file. The "true" parameter used in the constructor specifies that we want to append to the file (it will also create the file if it does not exist).

Then we generate the message and write it to the log file.

Note: this is a naive implementation of a file logger. There are several things to take into consideration before using something like this in production. Primarily, if the logging fails (such as if it doesn't have permissions to write the file), then an unhandled exception will be thrown. Logging is a complex topic, and we should seriously consider using a third-party logger for our applications. Other people have solved this problem already. We should take advantage of that.

Using the Exception Logging Decorator

Just as we did with the retry decorator, to use the exception logger we just need to snap our pieces together in a different order.

Here is the code with the ExceptionLoggingReader added (in the "PeopleViewer" project, App.xaml.cs file -- again this code is different from what is in the GitHub project):

Let's walk this code from the bottom up. The last line creates a MainWindow class (the view). The view constructor needs an IPeopleViewModel. So above that, we create a view model (PeopleReaderViewModel) to pass to the view constructor.

The PeopleReaderViewModel constructor needs an IPersonReader. Above that, we create an ExceptionLoggingReader to pass to the view model constructor.

The ExceptionLoggingReader constructor needs both an IPersonReader (the wrapped data reader) as well as an ILogger. So above that, we create a ServiceReader and a FileLogger.

To use the exception logging decorator, we simply snap our pieces together in a different order.

Running the Application (Failure)

To see the functionality in action, we will run the PeopleViewer application just like we did above.

When we click the "Refresh People" button (and then click "Continue" when the debugger stops), we get the error popup:

Just like before, we get the generic failure message. But now we have a log file to look at.

Viewing the Log

As we saw above, the FileLogger uses the same path as the executable. We can navigate to that location to see the log file.

Note: the way I get there is to right-click on the "PeopleViewer" project in the Visual Studio Solution Explorer, then select "Open Folder in File Explorer". From there, I just click into the "bin" folder, then the "Debug" folder.

In that folder we find the "ExceptionLog.txt" file. Here is the content:

This shows that we got an "HttpRequestException" since the web service was not running. We can also see the stack trace showing that the exception was thrown in the "ServiceReader.GetPeople" method which was called by the "ExceptionLoggingReader.GetPeople" method.

The log file has all of the details of the exception. So we can use this to see what is really happening in our system.

Unit Testing the Exception Logging Decorator

Before wrapping things up, let's look at how we can unit test the ExceptingLoggingReader class. This is fairly similar to how we tested the RetryReader.

Testing the Happy Path

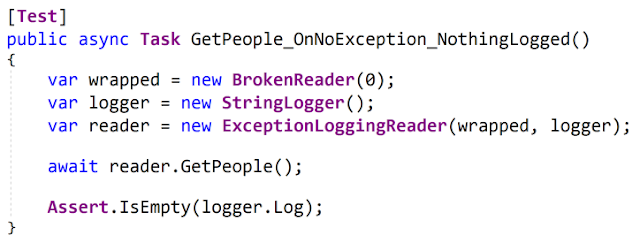

For the first test, we will check to make sure that nothing gets logged if the call returns successfully. Let's start by creating the objects. (The tests are in the "PersonReader.Decorators.Tests" project, ExceptionLoggingReaderTests.cs file.)

For this test, we can use the same BrokenReader fake class that we used for the RetryReader tests (see the previous article for details). When we pass "0" as a parameter, the calls will complete successfully (i.e., not broken).

A Fake Logger

When we create the ExceptionLoggingReader, we pass in the fake reader, but we also need an ILogger. We don't want to use the FileLogger because that would rely on the file system. Instead, I created an in-memory logger that can be used for testing.

This code is in the StringLogger.cs file (still in the same test project):

This class implements the "ILogger" interface, so it has the "LogException" and "LogMessage" methods.

At the top of the class is a public "Log" property. This is just a string to hold log messages. The methods append to this property. Since the property is public, we can inspect the value in our tests.

Note: these are asynchronous methods and must return a Task. An easy way to do this is with the "Task.CompletedTask" static property. This saves us from needing to create a new Task ourselves.

Finishing the First Test

With the fake logger in place, we can finish up the code for the first test (in the ExceptionLoggingReaderTests.cs file):

A new instance of the StringLogger is created for this test, so we know that the "Log" property will be empty when we start.

After calling the "GetPeople" method, we expect that the "Log" property will still be empty. And that is exactly what this test does.

Note: for more information on unit testing async methods, take a look at the previous article More DI: Unit Testing Async Methods.

Testing the Log

Now that we've tested that the ExceptionLoggingReader does nothing if there is no exception, let's test what happens if there *is* an exception.

Here is the test:

This test is set up a little bit different. First, notice that the "BrokenReader" constructor is passed a value of "1". This means that when we call the "GetPeople" method, we expect that it will be broken the first time. (And since we're only calling it once, this is all we need.)

The "expectedMessage" is set to an invalid value. The correct value should be set in the "catch" block as we'll see below. But if something goes wrong, we don't want our test to pass accidentally.

In the "try" block, we expect that the call to "GetPeople" will throw an exception. Because of this, I've added an "Assert.Fail" as a sanity check. If the "GetPeople" method does *not* throw an exception, then this block will get hit and the test will fail.

In the "catch" block, we look at the exception that is thrown. Since the ExceptionLoggingReader does not handle the exception, we will see it here. We can look at the exception message and use it as our "expectedMessage".

The assertion checks to see if the message from the exception we just caught is somewhere in the Log. If it is in the Log, then that means the exception was logged as expected.

Test Results

When we run these tests, we can see that they both pass:

Dependency Injection and the Decorator Pattern

Dependency Injection and the Decorator Pattern work really well together. Just like we saw with the RetryReader, we can use the ExceptionLoggingReader to injection functionality into our application. We just need to take our loosely coupled pieces and snap them together in a different order.

And since the decorator wraps an IPersonReader, it will work with any of our data readers (the ServiceReader, CSVReader, and SQLReader). And we did not need to modify any of our existing objects.

We did *not* need to change the view (MainWindow). We did *not* need to change the view model (PeopleReaderViewModel). We did *not* need to change the existing data reader (ServiceReader). We just snap our pieces together in a different order.

We can also stack our decorators so that decorators end up adding functionality to other decorators. This way we can add functionality a bit at a time, which makes it easier to test and also to combine in different ways depending on what our application needs. We will look at this in a future article.

Coming up, we will look at a CachingReader. This will add a client-side cache to the application. And as with our other decorators, we can get the functionality without modifying our existing objects. So be sure to stay tuned for more.

Happy Coding!

No comments:

Post a Comment