In my presentation "Unit Testing Makes Me Faster", I show a couple of videos that compare manual testing and unit testing. Folks have asked me to make these videos available, but they don't really make sense without context. So, we're going to look at both here.

The Method

Here's the method that we have in our code that needs to be tested:

The particulars aren't important. This method checks to see if a credit card number passes the Luhn algorithm -- basically a checksum on a credit card number. We need to make sure that this method works.

If you want to look at the code for this, you can get it here: Unit Testing Makes Me Faster.

Manual Testing

Before I started unit testing, I would commonly throw together a tester application just to sanity check the algorithm. This would be a simple application with some input/output fields and a button.

In this case, I built a little WPF application (since WPF is my UI of choice these days). This application just takes a few minutes to build, and we end up with something that looks like this:

The code-behind for the button calls our method and puts the results in an output block:

To use this application, we paste our test numbers into the text box, click the button, and then check the output. This will tell us whether the "PassesLuhnCheck" method returns true or false:

Unit Testing

Building unit tests for this method is pretty simple. We just create a method to check for "true" results and a method to check for "false" results. To make things easier, we can parameterize the methods so that we can check multiple numbers.

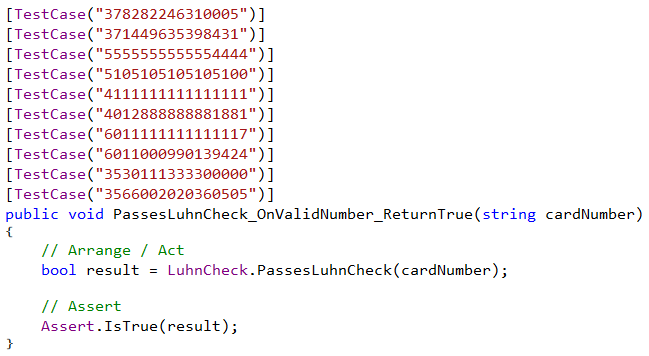

Here's our check for the numbers that should pass the Luhn check (and thus return "true"):

Because we're using parameterized tests, we can check 10 different cases with this one method.

For more information on parameterized tests, see Parameterized Tests with NUnit.

We can do the same for the numbers that should not pass the Luhn check:

This gives us 5 more test cases that should all return "false".

Build Comparison

And this takes us to the comparison videos. In the first video, we show side-by-side building the tester application and implementing the unit tests. This starts from scratch (File -> New Project) for both options.

So that we don't have to wait too long, this video is sped up 3 times faster than normal:

Direct video link: Side-By-Side Test Build

What this shows is that when we're comfortable with our tools, it takes about the same amount of time to build either test solution -- about 5 minutes in this case.

There is a big caveat there: when we're comfortable with our tools.

In my case, I am comfortable with WPF XAML and with unit testing using NUnit. If I did not know WPF, then I would expect that building the tester application would take me a bit longer. In the same way, if I were new to unit testing and NUnit, I would expect that building the unit tests would take me a bit longer.

But if I'm comfortable in both environments, then we get a fair comparison between these solutions.

The build times may be similar, but we see a real difference when we look at regression testing.

Regression Comparison

Regression testing is when we make sure that we didn't break any existing functionality in the code. It's a bit hard to tell in the above video, but we do have some failing tests. If the input contains a non-numeric (such as a letter or a minus sign), then the method we're testing throws an exception.

Our job is to fix the method so that our tests will pass (without throwing exceptions), and then we need to go back and check that we didn't break the existing functionality.

This video shows a side-by-side comparison of fixing the problem and then running regression tests. This video is *not* sped up; it is real time:

Direct video link: Side-By-Side Regression Test

This is where we see a huge difference. With our unit tests in place, after we make the change to our code, we simply build and re-run the tests. The tests take 3 seconds to run. We get confirmation that our changes fixed the problem and also that we didn't break the existing functionality.

For the manual test application, we need to go through our test cases and copy/paste them into the application and click the button. This only takes about a minute to do. But even so, it's painful to watch. If you watch closely, you'll see that the unit tests are complete before we have a chance to check the first value manually.

The real question is which type of regression are we most likely to do? If the tests run automatically in 3 seconds, then I'm going to be running those tests all day long. If I have to go through a manual process of copy/paste and clicking, then I'm never going to do that.

Wrap Up

Doing side-by-side comparisons of various testing methods can give us a good idea of where the advantages lie. Granted, it takes time to get up-to-speed on unit testing, but that's no different from any other framework. And there are many other advantages to having automated tests in place as well. Check out the materials for some more information: Unit Testing Makes Me Faster.

Happy Coding!

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

Saturday, November 21, 2015

Fixing an NUnit Version Mismatch

Sometimes demos don't always go according to plan.

But these steps did not work for me this past Wednesday. I added both NuGet packages, but the tests did not show up in the test explorer. Fortunately, I had a working solution that I prepared earlier, so we were able to continue with the demo.

The answer to the problem turned out to be pretty simple, but it wasn't something I could troubleshoot on the fly.

[Update 3/4/2016: A demonstration of installing NUnit in Visual Studio 2015 (including dealing with the current version mismatch) is available by watching a few minutes of this TDD video: TDD Bascis @ 3:30.]

[Update 04/20/2016: The 3.0 version of the Test Adapter has just been released. When using NUnit 3.0, be sure to use the "NUnit3TestAdapater" package from NuGet. When using NUnit 2.0, use the "NUnitTestAdapter" package from NuGet. More information here: Integrating NUnit into Visual Studio - Update for NUnit 3]

Version Mismatch

I suspected I might run into a problem when I saw the icons in NuGet:

I needed to add the first and third packages from this list. I noticed that the top one (the NUnit testing framework) had a new icon. And it didn't match the NUnitTestAdapter (the part that plugs into the Visual Studio Test Runner).

During the demo, I just hoped for the best. Unfortunately, this didn't work out so well.

Further Investigation

After the demo, I did some further investigation and found that the version numbers were, in fact, different.

NUnit 3.0 was *just* released. Unfortunately, the test adapter for version 3.0 had not yet been released (CTP 7 was available when I looked into this).

The Working Version

So one question is why did my pre-built version of the project work? Well, the NuGet packages that were saved off with the project were both for the 2.0 release of NUnit. Here's a screenshot from the video that shows the side-by-side build:

This has the icons that I was expecting to see on Wednesday. Since I didn't refresh my NuGet packages, I kept using the versions previously downloaded, and everything worked as expected.

As a reminder, you can see the videos and get other materials from the presentation on my website: Unit Testing Makes Me Faster.

Starting from Scratch

So the next question is how would we follow along with this sample if we wanted to start from scratch? The answer is that we just need to get the previous version of NUnit from NuGet.

In addition to the "Install" option in NuGet, we also have the option to "Downgrade":

When we do this, we can select the latest 2.0 version (2.6.4) or another version from the drop-down. If we install the 2.6.4 version of NUnit with the 2.0.0 version of the Test Adapter, then everything works as expected.

[Note: The latest NuGet package manager does not have a specific "Downgrade" option. Instead, you just pick the version you want from the "Version" drop-down, then click the "Install" or "Update" button.]

(An alternate solution is to get the pre-release version of the Test Adapter, but I don't normally use pre-release software. I like for other folks to shake out the bugs a bit first.)

This is a short-term problem. Hopefully in the very near future, the 3.0.0 version of the Test Adapter will be released, and we can go back to doing things the easy way.

Wrap Up

Things don't always go as we expect. And that's okay. But we should take the time to review what happened, try to figure out the core issue, and put steps in place to make sure it doesn't happen again.

In my case, I have another demo project that has the skeleton of the testing library. In that project, the NuGet packages for NUnit have already been included in the project. That means they don't need to download live, and we know that the version we have will work for the presentation. I actually already had this project so that I could still run this demo without a live internet connection, but I decided to take the chance at Live! 360 since I had good network access.

I had a great time presenting at Live! 360, and I'll look forward to coming back and doing it again.

Happy Coding!

Live coding demos pic.twitter.com/NyOMEb8ODS

— I Am Devloper (@iamdevloper) October 31, 2015

For those of you who were at Live! 360 this past week, I had a little trouble when I was showing how "easy" it is to get NUnit working in Visual Studio. Normally it is easy -- in fact, it's just as easy as this: Integrating NUnit into the Visual Studio Test Explorer.But these steps did not work for me this past Wednesday. I added both NuGet packages, but the tests did not show up in the test explorer. Fortunately, I had a working solution that I prepared earlier, so we were able to continue with the demo.

The answer to the problem turned out to be pretty simple, but it wasn't something I could troubleshoot on the fly.

[Update 3/4/2016: A demonstration of installing NUnit in Visual Studio 2015 (including dealing with the current version mismatch) is available by watching a few minutes of this TDD video: TDD Bascis @ 3:30.]

[Update 04/20/2016: The 3.0 version of the Test Adapter has just been released. When using NUnit 3.0, be sure to use the "NUnit3TestAdapater" package from NuGet. When using NUnit 2.0, use the "NUnitTestAdapter" package from NuGet. More information here: Integrating NUnit into Visual Studio - Update for NUnit 3]

Version Mismatch

I suspected I might run into a problem when I saw the icons in NuGet:

I needed to add the first and third packages from this list. I noticed that the top one (the NUnit testing framework) had a new icon. And it didn't match the NUnitTestAdapter (the part that plugs into the Visual Studio Test Runner).

During the demo, I just hoped for the best. Unfortunately, this didn't work out so well.

Further Investigation

After the demo, I did some further investigation and found that the version numbers were, in fact, different.

|

| NUnit framework version 3.0.0 |

|

| NUnit test adapter version 2.0.0 |

NUnit 3.0 was *just* released. Unfortunately, the test adapter for version 3.0 had not yet been released (CTP 7 was available when I looked into this).

The Working Version

So one question is why did my pre-built version of the project work? Well, the NuGet packages that were saved off with the project were both for the 2.0 release of NUnit. Here's a screenshot from the video that shows the side-by-side build:

|

| Previous NuGet packages showing 2.0 icons |

As a reminder, you can see the videos and get other materials from the presentation on my website: Unit Testing Makes Me Faster.

Starting from Scratch

So the next question is how would we follow along with this sample if we wanted to start from scratch? The answer is that we just need to get the previous version of NUnit from NuGet.

In addition to the "Install" option in NuGet, we also have the option to "Downgrade":

|

| Downgrade to Prior NUnit version |

When we do this, we can select the latest 2.0 version (2.6.4) or another version from the drop-down. If we install the 2.6.4 version of NUnit with the 2.0.0 version of the Test Adapter, then everything works as expected.

[Note: The latest NuGet package manager does not have a specific "Downgrade" option. Instead, you just pick the version you want from the "Version" drop-down, then click the "Install" or "Update" button.]

(An alternate solution is to get the pre-release version of the Test Adapter, but I don't normally use pre-release software. I like for other folks to shake out the bugs a bit first.)

This is a short-term problem. Hopefully in the very near future, the 3.0.0 version of the Test Adapter will be released, and we can go back to doing things the easy way.

Wrap Up

Things don't always go as we expect. And that's okay. But we should take the time to review what happened, try to figure out the core issue, and put steps in place to make sure it doesn't happen again.

In my case, I have another demo project that has the skeleton of the testing library. In that project, the NuGet packages for NUnit have already been included in the project. That means they don't need to download live, and we know that the version we have will work for the presentation. I actually already had this project so that I could still run this demo without a live internet connection, but I decided to take the chance at Live! 360 since I had good network access.

I had a great time presenting at Live! 360, and I'll look forward to coming back and doing it again.

Happy Coding!

Monday, November 9, 2015

Reference Types, Value Types, and Equality

In many places, we don't need to worry about the difference between value types and reference types. But one place we do see a difference is how equality is handled by default. I've had a couple of questions and comments about this recently, so let's take a closer look.

The Question

The questions came from my video series on Lambdas and LINQ (video playlist). There's also a print article available for download here: Learn to Love Lambdas (and LINQ, Too!).

Here's the code we're looking at:

This code refreshes the data in a list box by calling into a library that uses the Event Asynchronous Pattern (EAP). There's a particular piece of functionality we care about:

And then inside our lambda expression, we try to set the selected item in the list box:

The object that we have here (the "Person" class) does not have a primary key, so we compare the first name and last name properties -- this definitely isn't ideal, but it works for our small data set.

With this code in place, the selection will be saved between refreshes. So, if we run the application and select an item (Isaac Gampu), our screen looks like this:

(Notice the selection in the top left corner). Then when we change the sorting and click the "Refresh" button, we see that Isaac Gampu is still selected:

For more details on how the lambda expressions and LINQ methods work, be sure to check out the associated resources: Learn to Love Lambdas (and LINQ, Too!).

And this brings us to the question:

This makes our method much simpler:

This looks great (and sounds a lot easier). But unfortunately, it doesn't work. Here's what happens. First, we make an initial selection (John Sheridan):

Then when we click "Refresh", we lose our selection:

Why does this happen? For this we'll need to take a closer look at the difference between reference types and value types.

Reference Types, Value Types, and Equality

The difference between reference types and value types is how they are stored in memory. There are 2 memory locations we need to worry about: the stack and the heap.

I won't go into a full explanation of the stack and heap. You can get a good overview here: C# Heap(ing) and Stack(ing) in C#.

What's important to understand here is how equality is handled differently with reference types and value types.

Value Type Equality

Since value types are stored on the stack, equality is determined by comparing the values. This makes it easy to compare ints, bools, and chars. A struct is also a value type. Since a struct generally has multiple sub-values, equality is determined by comparing the values of each field and/or property.

Reference Type Equality

Since reference types are stored on the heap, equality is determined by looking at the pointer. If 2 objects point to the same object in memory, then they are considered to be equal. This means that they are only equal if they point to the same instance in memory.

But if we have 2 separate instances, then they will not be equal (at least with the default implementation; we'll look at another solution in just a bit).

Classes are reference types, so we end up running into this behavior quite a bit. Our "Person" is a class:

Observed Behavior

So why do we have a problem with our proposed code?

When we assign a value to the "SelectedItem" property of our list box, it looks through the items in the list to try to find one that is equal.

When we save off our "selectedPerson" object, we have an instance of the Person class (that holds "John Sheridan" in our example). When we reload our list box, we have a new collection of Person objects. One of those items has a value of "John Sheridan", but this is a different instance from the one that we saved off.

Because we have 2 different instances (the saved one and the one in the list), these are not considered to be equal. And that's why we get the observed behavior (no selection) instead of the expected behavior.

Now let's look at two solutions that will get our proposed code to work.

Option 1: Change Person to a Value Type

One option is to change the "Person" object from a reference type to a value type. In our case, this would involve changing it from a "class" to a "struct". The "Person" declaration is close to the same:

But because we just changed this to a value type, some of our other code breaks. Here's the updated code where we save off a copy of the selected item:

Since our "Person" is now a non-nullable value type, we need to treat it a little differently. The "as" operator only works with reference types since it can result in a null. So instead, we initialize "selectedPerson" to an empty "Person" object, then we make sure that the list box actually has a selected item. If it does, then we cast it to a "Person" and assign it to our variable.

The rest of the code stays the same. Here's our updated method:

And our behavior is as expected. If we run our application and select an item (Dave Lister):

And the click "Refresh", we see that our selected item is set appropriately:

Because we're dealing with value types, the comparison is done by looking at the values of the properties: first name, last name, start date, and rating. If these values all match, then the items are considered by be equal.

So we've seen how we can change our data object to a value type, and our proposed code works as expected. But what if we want to keep our "Person" as a class? There's an option for that, too.

Option 2: Override Equals()

Our second option is to keep "Person" as a class (a reference type). The default behavior of "Equals" is what we saw above -- it only returns true if we're comparing the same instance. But we can override the default behavior with something that is more appropriate to our situation. Here's the code for that:

Notice that we have a "class" here. Then we override the "Equals()" method. First we cast our parameter to a "Person". When we use the "as" operator, we will get a null if the cast fails. Next we check for a "null". This could be because another object type was passed in or a null parameter was passed in. If either of these is true, then we return false (meaning, not equal).

Finally, we set up our own equality comparison based on the key properties: first name, last name, and start date. (I didn't include the rating since that could be changeable.)

Then we can go back to our original proposed method:

If we run this code, we see that it works as expected. We can select an item (John Crichton):

And then after "Refresh", the item is still selected:

It would be nice if we could stop here, but things aren't quite so simple. If you notice in our "Person" class, we have a green squiggly. This tells us that there's a warning. We can see this in our build results:

This tells us that whenever we override "Equals()", we should also override "GetHashCode()". The hash code is used when we use this class as a key in a Dictionary. There are rules about creating hash codes that become important depending on how we're using the object. You can get more information on this here: MSDN Object.GetHashCode() Method.

Another thing that we should do when we override "Equals()" is to provide a generic version for our specific type: "Equals<Person>(Person obj)". But we won't do that today either.

As we can see, once we start going down the path of changing how equality works with an object, we have quite a bit of work to do.

Original Code

One of the questions that I received on the original code:

But the bigger reason is that we don't always have the option of changing our data objects. Even when we're constrained by our data, we can use LINQ to query it, filter it, sort it, and even easily locate items in a list.

Wrap Up

We don't usually have to worry about the difference between reference types and value types. But as we've seen, there is a big difference between them when we start to talk about equality comparisons. As usual, there are several different ways that we can approach the problem. And that's good. When we have options, we are free to select whichever one works best for our particular situation.

Happy Coding!

The Question

The questions came from my video series on Lambdas and LINQ (video playlist). There's also a print article available for download here: Learn to Love Lambdas (and LINQ, Too!).

Here's the code we're looking at:

This code refreshes the data in a list box by calling into a library that uses the Event Asynchronous Pattern (EAP). There's a particular piece of functionality we care about:

- Before refreshing the list box, we save off a copy of the currently selected item.

- After refreshing the list box, we try to set the selected item based on our saved value.

And then inside our lambda expression, we try to set the selected item in the list box:

|

| Set Selected Item in List Box |

With this code in place, the selection will be saved between refreshes. So, if we run the application and select an item (Isaac Gampu), our screen looks like this:

|

| Initial Selection - Isaac Gampu |

|

| Isaac Gampu still selected after refresh |

And this brings us to the question:

Why can't we just set the selected item directly based on our saved person?The proposal is to replace the code above ("Set selected item in list box") with the following:

This makes our method much simpler:

This looks great (and sounds a lot easier). But unfortunately, it doesn't work. Here's what happens. First, we make an initial selection (John Sheridan):

|

| Initial Selection - John Sheridan |

|

| No selection after Refresh |

Reference Types, Value Types, and Equality

The difference between reference types and value types is how they are stored in memory. There are 2 memory locations we need to worry about: the stack and the heap.

I won't go into a full explanation of the stack and heap. You can get a good overview here: C# Heap(ing) and Stack(ing) in C#.

What's important to understand here is how equality is handled differently with reference types and value types.

Value Type Equality

Since value types are stored on the stack, equality is determined by comparing the values. This makes it easy to compare ints, bools, and chars. A struct is also a value type. Since a struct generally has multiple sub-values, equality is determined by comparing the values of each field and/or property.

Reference Type Equality

Since reference types are stored on the heap, equality is determined by looking at the pointer. If 2 objects point to the same object in memory, then they are considered to be equal. This means that they are only equal if they point to the same instance in memory.

But if we have 2 separate instances, then they will not be equal (at least with the default implementation; we'll look at another solution in just a bit).

Classes are reference types, so we end up running into this behavior quite a bit. Our "Person" is a class:

Observed Behavior

So why do we have a problem with our proposed code?

When we assign a value to the "SelectedItem" property of our list box, it looks through the items in the list to try to find one that is equal.

When we save off our "selectedPerson" object, we have an instance of the Person class (that holds "John Sheridan" in our example). When we reload our list box, we have a new collection of Person objects. One of those items has a value of "John Sheridan", but this is a different instance from the one that we saved off.

Because we have 2 different instances (the saved one and the one in the list), these are not considered to be equal. And that's why we get the observed behavior (no selection) instead of the expected behavior.

Now let's look at two solutions that will get our proposed code to work.

Option 1: Change Person to a Value Type

One option is to change the "Person" object from a reference type to a value type. In our case, this would involve changing it from a "class" to a "struct". The "Person" declaration is close to the same:

But because we just changed this to a value type, some of our other code breaks. Here's the updated code where we save off a copy of the selected item:

Since our "Person" is now a non-nullable value type, we need to treat it a little differently. The "as" operator only works with reference types since it can result in a null. So instead, we initialize "selectedPerson" to an empty "Person" object, then we make sure that the list box actually has a selected item. If it does, then we cast it to a "Person" and assign it to our variable.

The rest of the code stays the same. Here's our updated method:

And our behavior is as expected. If we run our application and select an item (Dave Lister):

|

| Initial Selection - Dave Lister |

|

| Dave Lister still selected after Refresh |

So we've seen how we can change our data object to a value type, and our proposed code works as expected. But what if we want to keep our "Person" as a class? There's an option for that, too.

Option 2: Override Equals()

Our second option is to keep "Person" as a class (a reference type). The default behavior of "Equals" is what we saw above -- it only returns true if we're comparing the same instance. But we can override the default behavior with something that is more appropriate to our situation. Here's the code for that:

Notice that we have a "class" here. Then we override the "Equals()" method. First we cast our parameter to a "Person". When we use the "as" operator, we will get a null if the cast fails. Next we check for a "null". This could be because another object type was passed in or a null parameter was passed in. If either of these is true, then we return false (meaning, not equal).

Finally, we set up our own equality comparison based on the key properties: first name, last name, and start date. (I didn't include the rating since that could be changeable.)

Then we can go back to our original proposed method:

If we run this code, we see that it works as expected. We can select an item (John Crichton):

|

| Initial Selection - John Crichton |

And then after "Refresh", the item is still selected:

|

| John Crichton still selected after Refresh |

This tells us that whenever we override "Equals()", we should also override "GetHashCode()". The hash code is used when we use this class as a key in a Dictionary. There are rules about creating hash codes that become important depending on how we're using the object. You can get more information on this here: MSDN Object.GetHashCode() Method.

Another thing that we should do when we override "Equals()" is to provide a generic version for our specific type: "Equals<Person>(Person obj)". But we won't do that today either.

As we can see, once we start going down the path of changing how equality works with an object, we have quite a bit of work to do.

Original Code

One of the questions that I received on the original code:

Why didn't you just override the Equals method?There are a couple of reasons for this. The first reason is that we lose the lambda expressions and LINQ methods that I wanted to demonstrate here ☺.

But the bigger reason is that we don't always have the option of changing our data objects. Even when we're constrained by our data, we can use LINQ to query it, filter it, sort it, and even easily locate items in a list.

Wrap Up

We don't usually have to worry about the difference between reference types and value types. But as we've seen, there is a big difference between them when we start to talk about equality comparisons. As usual, there are several different ways that we can approach the problem. And that's good. When we have options, we are free to select whichever one works best for our particular situation.

Happy Coding!